QUINCY JONES' VIDEO NETWORK

FOR BLACK music & GLOBAL sounds

Try 7 days free

the best seat

in the house

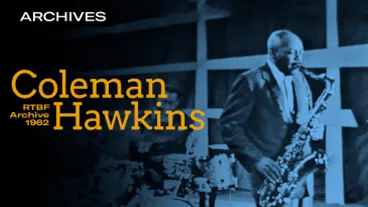

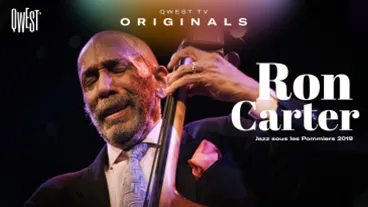

Enjoy a selection of premium documentaries, concerts, archive gems and interviews. Curated by Quincy Jones, music icons and a team of experts.

the best seat

in the house

Enjoy a selection of premium documentaries, concerts, archive gems and interviews. Curated by Quincy Jones, music icons and a team of experts.

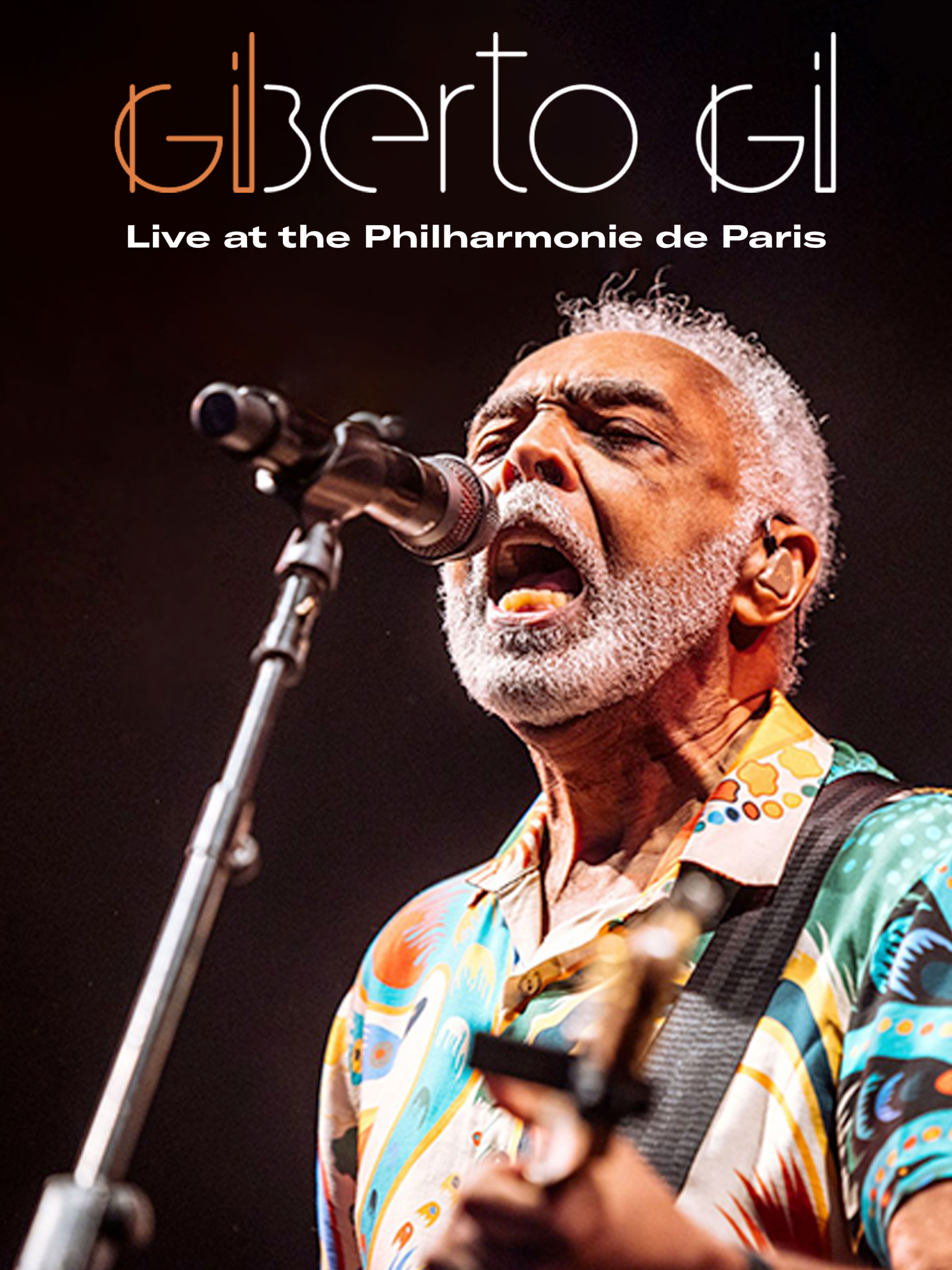

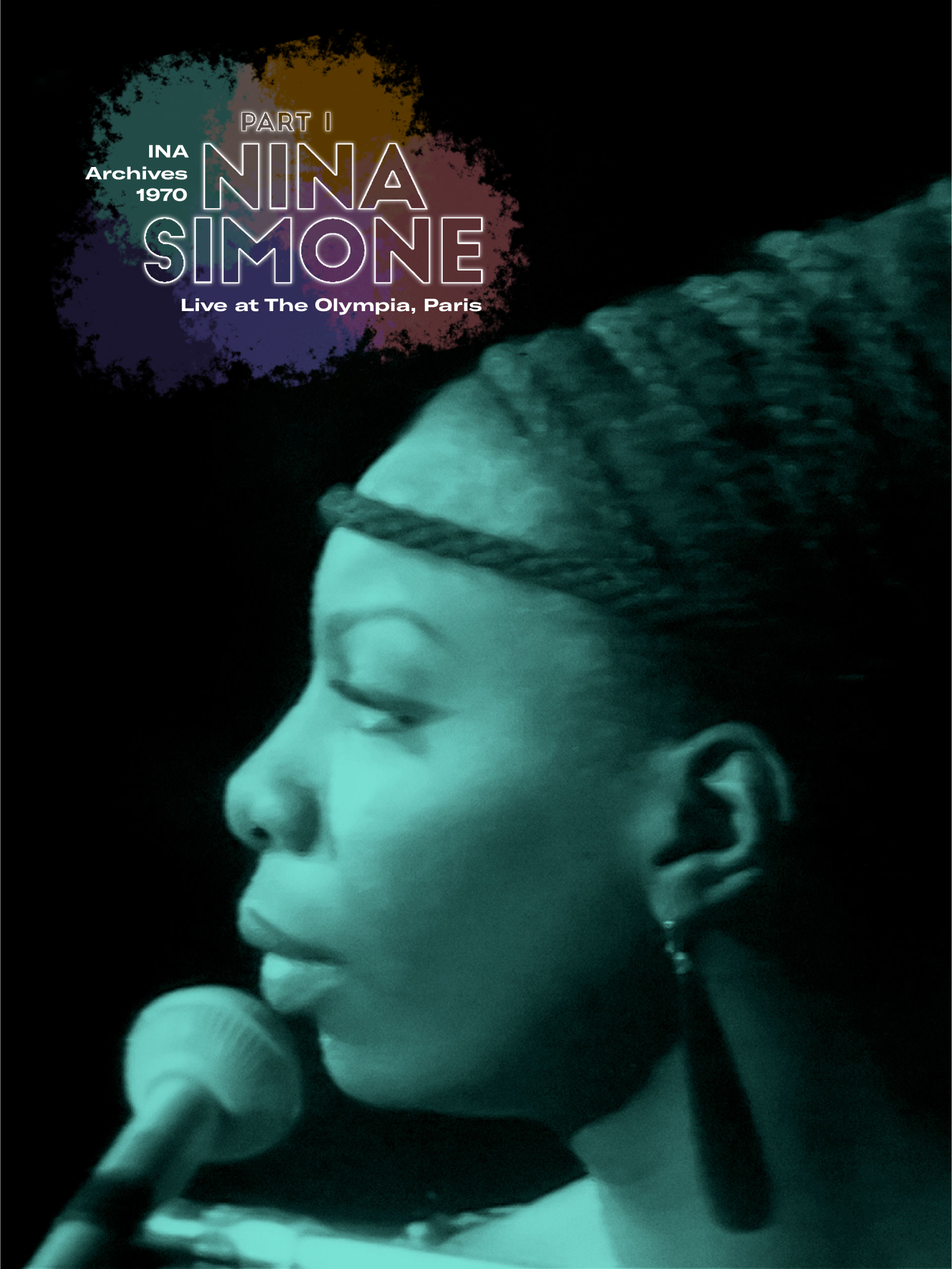

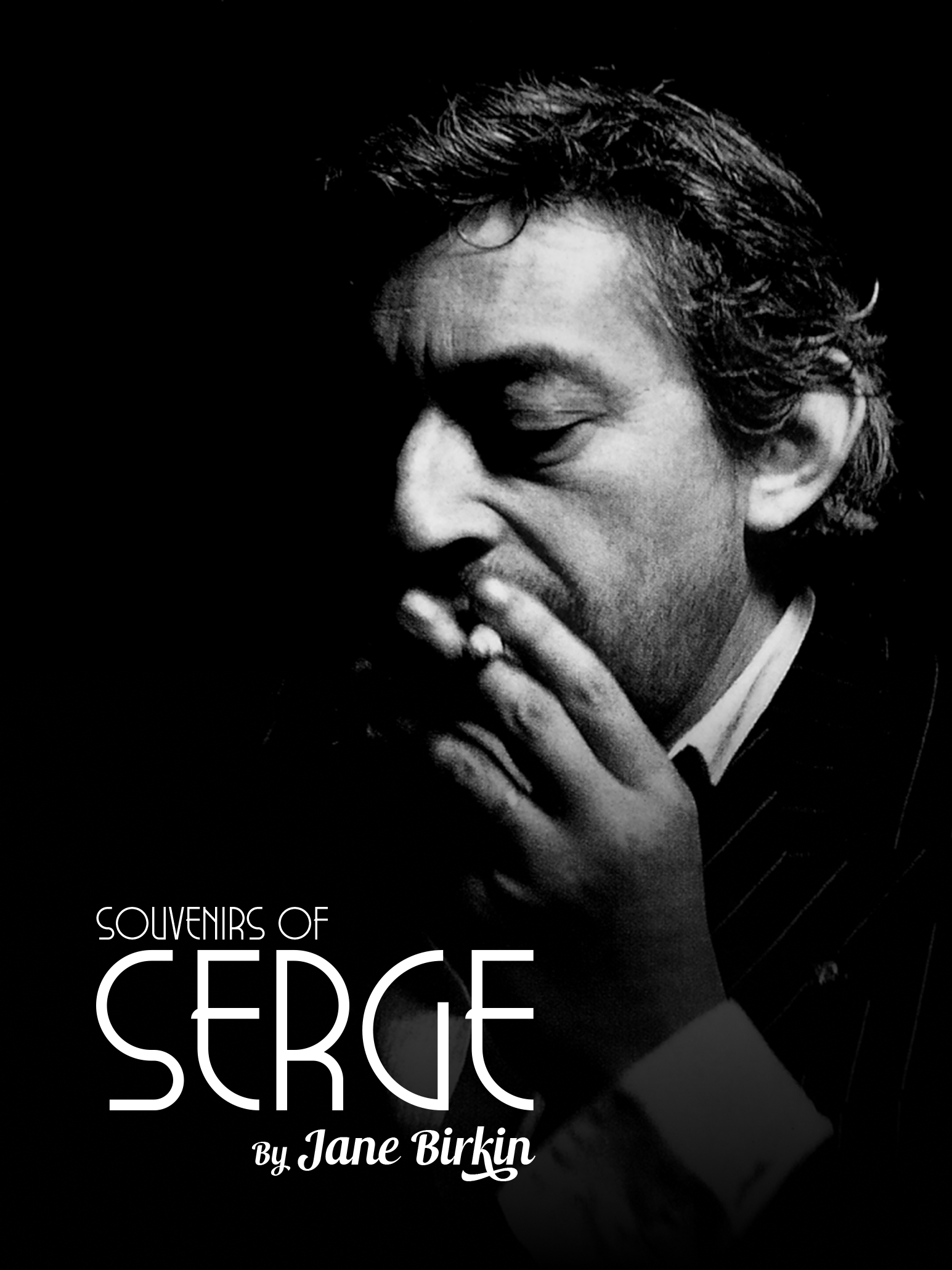

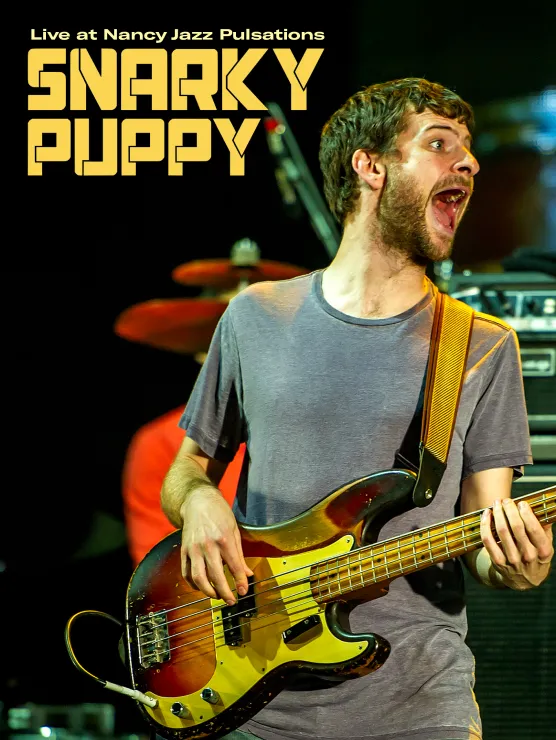

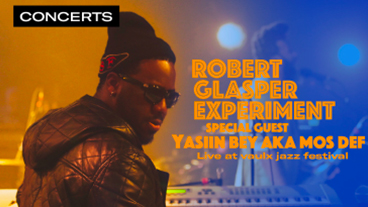

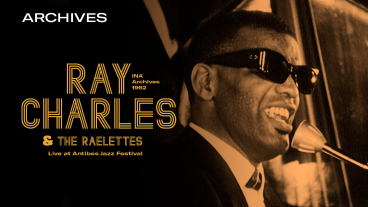

new releases

your groove

select a plan and let the music move you.

- +1300 contents

- HD or 4k

- Compatible w/ TV, computer, smartphone or tablet

- cancel anytime

where the artists

are also fans

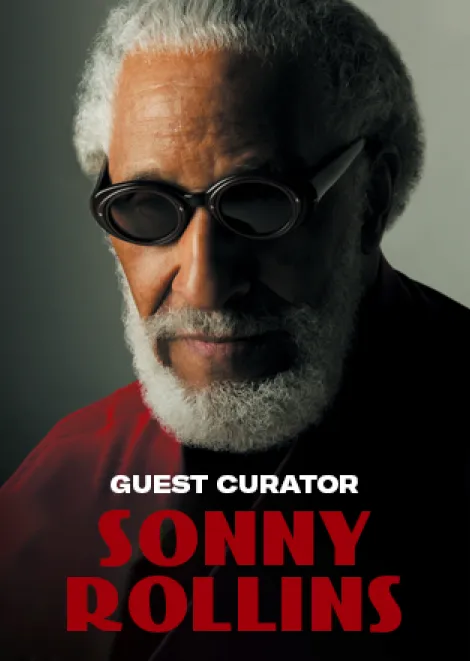

Qwest TV is a community that hears it differently. Here’s what the legends are watching...

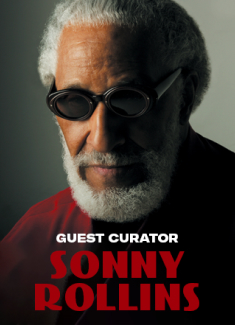

sonny rollins PERSONAL PLAYLIST

Daptone Recording Co. PERSONAL PLAYLIST

Gregory porter'S PERSONAL PLAYLIST

carl craig'S PERSONAL PLAYLIST

anoushka shankar'S PERSONAL PLAYLIST

“Qwest TV, a platform that provides listeners with a new and approachable way to discover the music that they were never formally introduced to. It’s time to break down the barriers for any willing ear, and Qwest TV is here to help bring you to new uncharted musical territories!”

FAQ

What is Qwest TV?

How much does Qwest TV cost?

How to watch Qwest TV?

What can I watch on Qwest TV?

Let’s groove tonight? Get your free trial.